Ever wondered how the layers of Earth tell stories from millions of years ago? Sedimentary rocks, with their distinctive layers and hidden secrets, are like pages of an ancient journal. They whisper tales of rivers that once roared, seas that receded, and creatures that roamed long before us. Understanding sedimentary rocks isn’t just for geologists—it’s a fascinating way to connect with Earth’s past.

What Are Sedimentary Rocks?

Sedimentary rocks form when particles, like sand, silt, and organic matter, are compacted and cemented over time. Imagine a time-lapse of a beach where the grains of sand eventually turn into stone—voilà, you’ve got a sedimentary rock!

Definition of Sedimentary Rocks

At their core, sedimentary rocks are formed from sediments—small fragments of pre-existing rocks, minerals, or organic materials. These sediments accumulate in layers and undergo processes like compaction and cementation to solidify into rock.

Think of them as nature’s recyclers. When mountains erode, or rivers carry sand to the ocean, those fragments don’t just disappear. Instead, they get repurposed into new rocks, preserving a snapshot of the environment they came from.

Characteristics of Sedimentary Rocks

Sedimentary rocks are layered, which gives them a unique, striated appearance. These layers, or strata, are like a timeline, recording changes in the Earth’s environment over millennia.

Other key features include:

- Fossils: Many sedimentary rocks, like limestone and shale, are treasure troves of ancient life. Fossils within these rocks help scientists understand extinct species and ecosystems.

- Porosity: Many sedimentary rocks, like sandstone, are porous, making them ideal for storing water, oil, and natural gas.

Importance of Sedimentary Rocks

Why should we care about sedimentary rocks? Glad you asked! Here’s why:

- They make up about 75% of Earth’s surface rocks. So, chances are, if you’ve picked up a rock, it’s sedimentary.

- Economic significance: Many are rich in natural resources like oil, coal, and natural gas.

- Historical records: They provide clues about past climates, geological events, and even asteroid impacts!

The Formation Process of Sedimentary Rocks

Understanding how sedimentary rocks form is like uncovering the recipe for one of Earth’s most fascinating creations. The process is intricate, yet remarkably logical, following a series of steps that begin with tiny particles and end with solid rock.

Step-by-Step Overview

1. Weathering and Erosion:

Sedimentary rocks start with the breakdown of existing rocks. Weathering—caused by wind, water, temperature changes, and even plants—breaks rocks into smaller fragments. Once broken, these fragments are carried away by erosion, like crumbs swept off a table. Rivers, glaciers, and wind do the heavy lifting here, transporting sediments far from their source.

2. Transportation of Sediments:

As sediments are carried, their size and shape change. Large, jagged pieces might tumble down a river, while finer particles like silt float along. Over time, these fragments settle in specific environments, like riverbeds, deltas, or ocean floors.

3. Deposition:

Sediments eventually come to rest when the transporting medium (like water or wind) slows down. Picture a river emptying into a lake: the larger, heavier particles drop first, while lighter particles settle farther out. This creates distinct layers, or strata, a hallmark of sedimentary rocks.

4. Compaction:

Over thousands—or even millions—of years, layers of sediment pile on top of each other. The weight of the upper layers compresses the lower ones, squeezing out water and reducing the space between particles.

5. Cementation:

Finally, minerals like quartz or calcite seep between the compressed particles, binding them together. This step turns sediment into a cohesive rock, solidifying the process.

The Role of Sediments

Sediments are the building blocks of sedimentary rocks, and their variety adds richness to the final product. Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Clastic sediments (sand, gravel, clay) create rocks like sandstone and shale.

- Chemical sediments form when dissolved minerals precipitate out of water, making rocks like limestone.

- Organic sediments, such as plant debris, lead to coal or oil shale.

The composition, size, and arrangement of these sediments determine the type of sedimentary rock formed.

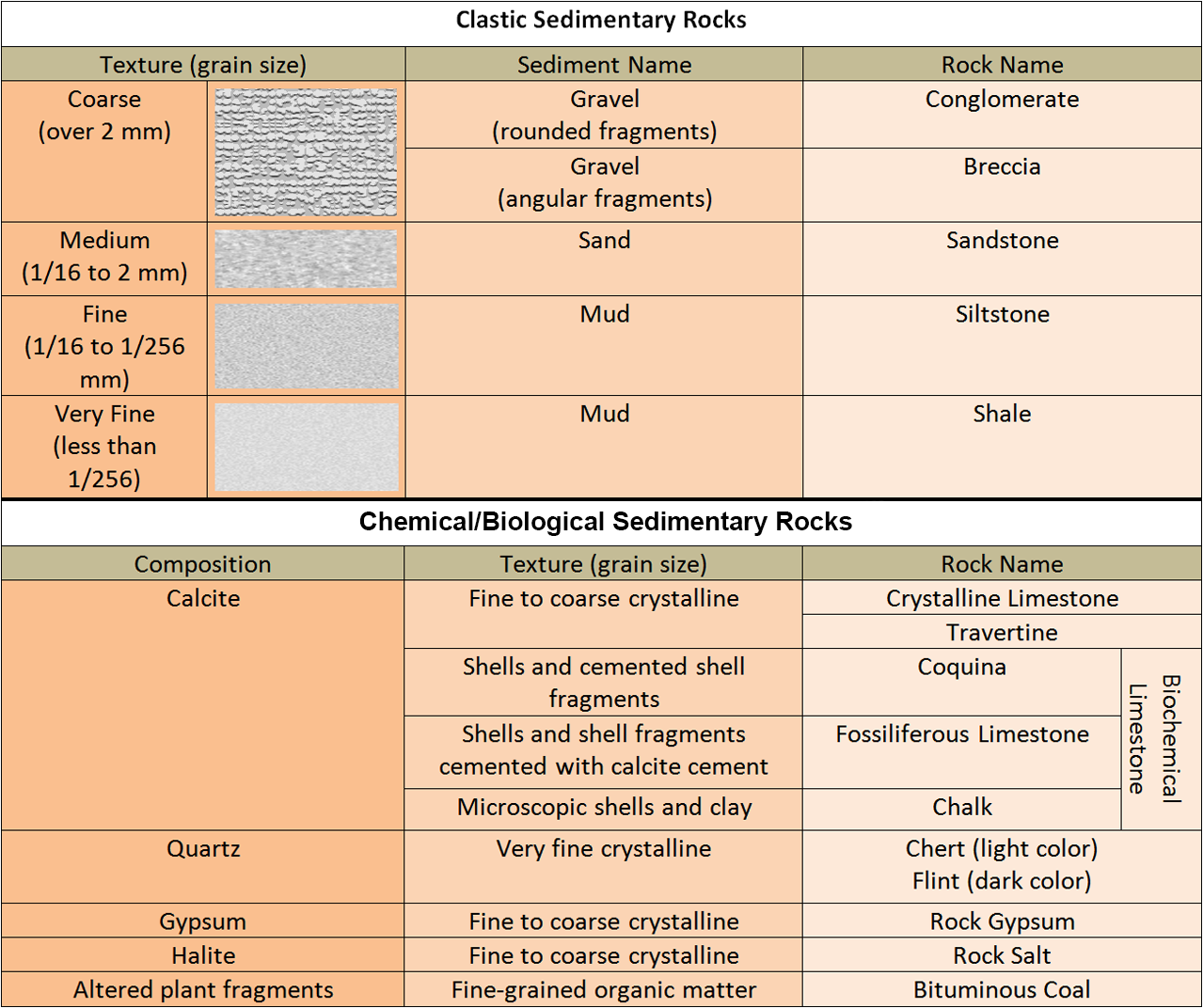

Sediment Size and Corresponding Rock Types

| Sediment Size | Rock Type | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse (gravel) | Conglomerate | River deposits |

| Medium (sand) | Sandstone | Desert dunes |

| Fine (silt/clay) | Shale | Quiet lakebeds |

| Chemical precipitates | Limestone/Evaporites | Shallow seas, caves |

| Organic matter | Coal/Oil shale | Swamps, bogs |

Sedimentary rock formation is a slow, patient process. It’s a bit like baking—except instead of hours, it takes millions of years, and instead of heat, the ingredients are compressed by time and pressure.

What Are the 5 Main Types of Sedimentary Rocks?

Now that we’ve explored how sedimentary rocks form, let’s dive into the stars of the show: the five main types of sedimentary rocks. Each type has unique characteristics, formation processes, and uses, making them crucial in geology and beyond.

1. Clastic Sedimentary Rocks

Clastic sedimentary rocks are like mosaics made from broken pieces of other rocks. The term “clastic” comes from the Greek word for “broken,” which perfectly describes how these rocks are formed.

Formation Process:

Clastic rocks form when fragments of pre-existing rocks (clasts) are transported, deposited, and then compacted and cemented. The size and shape of the clasts determine the type of rock that forms. For instance:

- Sand-sized particles form sandstone.

- Clay-sized particles create shale.

- Pebbles and larger fragments result in conglomerates (if rounded) or breccias (if angular).

Examples and Uses:

- Sandstone: Found in deserts, beaches, and riverbeds, sandstone is a popular building material thanks to its durability and workability.

- Shale: Often rich in fossils, shale is used in ceramics and as a source of oil and natural gas.

Fun Fact:

Some sandstones contain quartz grains that are older than the Earth’s oldest known rocks. Talk about ancient relics!

2. Chemical Sedimentary Rocks

Chemical sedimentary rocks form when minerals precipitate out of a solution, typically water. They often form in environments like caves or evaporative basins.

Formation Process:

When water evaporates or becomes supersaturated, dissolved minerals crystallize and form rock. This can happen in:

- Shallow seas where evaporation is high (e.g., the Dead Sea).

- Underground caves where mineral-laden water drips, forming stalactites and stalagmites.

Examples and Uses:

- Limestone: Formed mainly from calcite, limestone is used in cement, as a building material, and in agriculture to neutralize acidic soils.

- Halite (rock salt): An essential resource for food preservation, de-icing roads, and even manufacturing.

Case Study:

The Great Salt Lake in Utah is a modern example of how evaporative processes create halite deposits. Imagine walking on what feels like a giant, crunchy salt flat!

3. Organic Sedimentary Rocks

Organic sedimentary rocks are the result of accumulated biological material—like plant debris or animal remains—that gets compacted over time. These rocks are fossil fuels in disguise.

Formation Process:

Organic matter, such as plants in swampy areas, doesn’t decompose fully due to lack of oxygen. Over time, layers of this organic material are buried, heated, and transformed into rock.

Examples and Uses:

- Coal: Formed from ancient plant material, coal is a vital energy resource and a reminder of lush prehistoric landscapes.

- Oil shale: A source of hydrocarbons, oil shale is created from microscopic algae and organic matter.

Did You Know?

Some coal deposits are so ancient they predate the dinosaurs, hailing from the Carboniferous Period (over 300 million years ago).

4. Biochemical Sedimentary Rocks

Biochemical rocks form through the activities of living organisms. These rocks are essentially ecosystems turned to stone.

Formation Process:

Organisms like corals, shellfish, and plankton extract calcium carbonate from seawater to form their shells and skeletons. When these organisms die, their remains accumulate on the ocean floor and eventually turn into rock.

Examples and Uses:

- Fossiliferous limestone: Contains visible fossils, making it a favorite for paleontologists and geologists alike.

- Chalk: Made of microscopic plankton shells, chalk is used in classrooms (of course!) and even as a mild abrasive in household cleaners.

Interesting Tidbit:

The White Cliffs of Dover in England are made of chalk, composed of countless microscopic fossils deposited over millions of years.

5. Evaporites

Evaporites form in areas where water evaporates rapidly, leaving behind mineral deposits. Think salt flats and desert basins.

Formation Process:

As water evaporates in hot, arid climates, dissolved minerals like halite and gypsum crystallize and accumulate. These rocks are often found in places that were once ancient lakes or seas.

Examples and Uses:

- Rock salt: Besides its culinary fame, it’s also essential for de-icing and chemical production.

- Gypsum: Used in making plaster, drywall, and even toothpaste!

Fascinating Fact:

The Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah are a famous natural example of an evaporite deposit. They’re so flat and vast that they’re used for high-speed car races!

Each type of sedimentary rock tells a unique story of Earth’s history. From sand dunes turning to sandstone to ancient swamps becoming coal, these rocks are Earth’s time capsules, offering glimpses into environments that existed long before our time.

How to Identify Sedimentary Rocks

Identifying sedimentary rocks is like being a detective piecing together clues about the Earth’s history. Each rock carries hints about its origin, composition, and environment of formation. Whether you’re a geology student or just someone curious about the stones you’ve stumbled upon, here’s how to identify sedimentary rocks with confidence.

Physical Properties to Look For

1. Texture:

Sedimentary rocks have distinct textures that can help you differentiate between types:

- Grain size: Ranges from coarse (gravel) to fine (clay). Coarse-grained rocks like conglomerates feel gritty, while fine-grained rocks like shale feel smooth.

- Grain shape: Rounded grains indicate long-distance transport (as in conglomerates), while angular grains suggest a shorter journey (as in breccias).

- Sorting: Well-sorted grains are uniform in size (common in beach environments), whereas poorly sorted grains vary widely in size (often found in landslide deposits).

2. Color:

The color of a sedimentary rock can reveal its chemical composition and the conditions under which it formed:

- Red or brown hues suggest the presence of iron oxides and oxygen-rich environments.

- Black or dark gray indicates high organic content or low-oxygen conditions, typical of swamps or deep oceans.

3. Layering (Stratification):

Most sedimentary rocks exhibit clear layers or strata. These layers represent different periods of deposition, much like the pages of a book.

Tools and Techniques for Identification

1. Hand Lens or Microscope:

A closer look at the rock’s surface can reveal fine details about grain size, shape, and mineral composition. For instance:

- A sandstone under a lens often reveals quartz grains bound by a cementing material.

- Shale may show tiny, tightly packed clay particles.

2. Acid Test:

A simple drop of dilute hydrochloric acid can be a game-changer:

- Rocks like limestone and chalk, rich in calcium carbonate, fizz vigorously.

- Other sedimentary rocks, like sandstone or shale, typically show no reaction.

3. Hardness Test:

Sedimentary rocks vary in hardness:

- Soft rocks like shale can be scratched with a fingernail.

- Harder rocks like quartz sandstone require a steel blade to leave a mark.

4. Fossil Content:

Fossils, from shells to plant impressions, are a dead giveaway for sedimentary rocks. Limestone and shale are particularly rich in these ancient remains.

Key Features for Common Sedimentary Rocks

| Rock Type | Texture | Color | Fossil Presence | Acid Test Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandstone | Coarse-grained | Varies (yellow, red) | Rare | None |

| Shale | Fine-grained | Dark (gray, black) | Common | None |

| Limestone | Fine to coarse | Light (white, gray) | Very common | Fizzes vigorously |

| Conglomerate | Coarse, rounded grains | Varies | Rare | None |

| Coal | Smooth, lightweight | Black | Rare plant material | None |

Pro Tips for Beginners

- Feel the surface: Sandstone often feels gritty, while limestone is smoother.

- Observe in sunlight: Wetting the rock can help highlight its layers or grains.

- Think about the environment: A rock found in a riverbed is more likely clastic, while one near a salt flat could be an evaporite.

Remember, if your rock doesn’t fizz in an acid test, don’t worry—it’s just playing hard to get.